This blog is part one of a two-part series.

Software as a Service (SaaS) offers many advantages compared to on premise software for the commercial industry and the Federal Government. SaaS software can be deployed rapidly, you only pay for what you consume, and it typically requires less maintenance than on-premise software. It has become the bedrock of the industry and it is hard to imagine a software company developing new software without the intention of delivering it as a SaaS service. With these advantages, it is easy to understand why the global SaaS market size was valued at USD 261.15 billion in 2022 and is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 13.7% from 2023 to 2030[1]. That explains why there are now 30,000 SaaS companies and why the average commercial company has 130 SaaS applications in production[2]. It is predicted that the cloud will power 75% of software by 2030[3].

With all those applications, it is a wonder that by December 2023, only 320 applications had been approved for use by the Federal Government under its FedRAMP program. The DoD, which has its own set of standards beyond FedRAMP, is estimated to have less than 10% of the applications that have FedRAMP approval. As a result, federal agencies, who are already struggling to modernize legacy architectures, have nowhere to turn for modernization, and commercial companies with innovative new products are blocked from doing business with the federal government.

But what does this mean for startups? In part one of this two-part series, I’ll dig into the in’s and out’s of FedRAMP, breaking down the hurdles startups have to clear in the federal marketplace.

Why did we need FedRAMP?

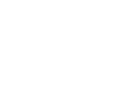

It is worthwhile to review the impetus for the FedRAMP program which brings us to the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA). FISMA is a United States federal law enacted in 2002 that requires all federal agencies to develop, document, and implement an information security and protection program. It specifies a set of security controls which each Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) must attest to for each application that it implements. There is a lot to FISMA, but what is important is that there are over 400 distinct and specific security controls that a CISO must attest to prior to granting an “Authorization to Operate” (ATO) and implementing the software application. An ATO can take months or even a year to review and achieve and is granted at the discretion of the CISO. The CISO does not need to share his “exceptions” or justifications for the security controls. He or she decides what is an acceptable risk for the agency.

Figure 1 The security controls by family, associated with FISMA and FedRAMP

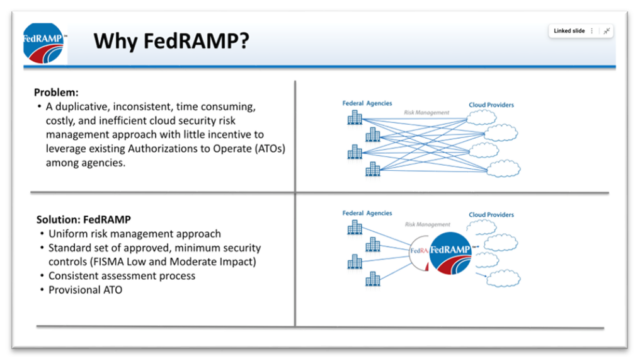

As the cloud became more popular, each CISO was doing his or her own evaluation and certification of a Cloud Service Provider (CSP). Many CISO’s were simultaneously repeating the same work for a particular cloud service. The GSA stepped in, and along with the Department of Defense (DOD) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), they created FedRAMP. The idea for FedRAMP was to certify once and deploy often. Rather than have each CISO do duplicative work, one CISO would certify the cloud application and others would benefit from their assessment. On the surface, this makes perfect sense. There’s no reason for many CISOs to review the same cloud software. Afterall, they’re evaluating the same software against the same security controls so why repeat the process many times?

Figure 2 FedRAMP was created to eliminate the duplicative approach of each agency reviewing the same piece of software. The idea was to “expedite the process”

Becoming FedRAMP Compliant

Achieving FedRAMP compliance is a massive undertaking for any vendor including the CSP’s. You begin by hiring a compliance team who is familiar with the regulations and process. You reengineer your product to meet the Federal requirements. You then need to hire a company to do penetration testing. After that, you hire another company that acts as the government’s agent, reviewing your 500 pages of documentation and validating it. That group is called a 3rd Party Assessment Organization (3PAO). The overall process can take over a year or even 18 months and can easily cost millions of dollars. Larger companies can easily make that investment, but it is a tall order for many of the SaaS vendors, especially startups, that are available on the market.

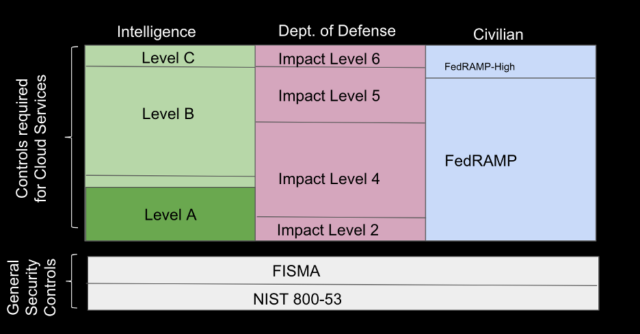

Boom! You overcome that hurdle and you have opened the large Federal market for your product. But not so fast! FedRAMP only applies to some of the Civilian agencies. Some Federal agencies require a higher degree of security and isolation because their data is more sensitive. So, we have another regulation called “FedRAMP High”, which specifies more security controls or in some cases, more rigorous implementations of some of the controls. This is another certification, costing most vendors millions of dollars and an additional 18 months to complete. FedRAMP High is usually deployed in completely different cloud regions known as GovClouds, with greater isolation, whereas FedRAMP applications commonly run in “commercial” clouds. For SaaS vendors, this means another expense as each region represents a different “data center” requiring another installation and another site to maintain.

So, you achieve FedRAMP High with your SaaS application. Now, the whole Federal market must be open to your solution… What’s that? The DoD doesn’t recognize the FedRAMP or the FedRAMP high certification? But I thought you said that the DoD was part of the group that developed the FedRAMP standard? And the DoD is on the Joint Authorization Board (JAB) approving FedRAMP compliance. Nonetheless, DoD has their own standards and they do not recognize FedRAMP as a secure environment.

That’s ironic, because the DoD’s regulations are based on the same FISMA security controls with some of the controls more rigorously enforced, but they’ve produced their own compliance requirements. The “Security Requirements Guide” (SRG) originally specified 6 different levels of compliance depending on the sensitivity of the data, ranging from Impact Level 1 to Impact Level 6. They’ve eliminated some of those levels and we are left with IL-2, IL-4, IL5, and IL-6. Each of these levels requires a different certification. And get this…. IL-6 is for “classified” workloads. That is another region, and your team needs to have a US Government secret clearance to install and maintain that region. The clearance process also requires sponsorship and can often take 6 months or a year.

Now, you have finally got access to the entire Government. What? The Intelligence Community has their own compliance? And their own regions? They refer to theirs as Intelligence Community Directive 503 or ICD-503. And within the intelligence community they have at least 3 additional levels of compliance.

So, now we’re up to 9 different certifications/compliances, running in at least 4 different regions, commercial, GovCloud, Secret region, and the top-secret region.

Figure 3 The different compliance levels with each box representing the relative size of the market.

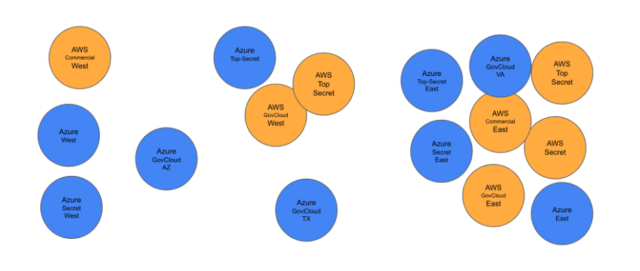

Finally, you’ve gotten through all the compliances. Your SaaS company has doled out millions and millions of dollars to meet all the Federal requirements and you’ve achieved all of these levels of compliance in all of Amazon Web Services’ (AWS) many regions. You’ve finally opened up the Federal market to your product. Until you talk to the next Federal agency who tells you that they don’t use AWS, but rather, Microsoft’s Azure. Now, you repeat everything that you just did for AWS and try to replicate it on Microsoft’s many clouds and regions. You think, well, I’ve already achieved compliance on AWS. It’s the same software. There must be an accelerated path to do this same thing on a different cloud. Nope. And after you’re done with Microsoft, do it all over again on Google Cloud Platform. And maybe Oracle Cloud after that. Had enough?

It doesn’t get better from there. It turns out that if you want to run your cloud with high availability or low latency, you really need to run in two regions (data centers) in distributed parts of the country. So, double the number of regions and double your costs. Each region can cost a company one million dollars a year to support and maintain.

Figure 4 The regions that a SaaS company would need to deploy in to satisfy all Federal requirements on Azure and AWS. Each region can cost as much as $1M to host and maintain.

One tiny thing I forgot to mention. Each one of these compliances needs to be “sponsored” by a Federal agency. You can’t achieve compliance without sponsorship. It turns out that sponsorship is not trivial for the Federal agency. They must read and attest to your 500 pages of documentation and the sponsoring CISO signs that and sends it to the FedRAMP office for all agencies to see. He or she puts their signature on the line stating the compliance of this software. That’s a big job and an even bigger responsibility for the CISO and they have no obligation or mandate to sponsor companies. Federal agencies are not staffed to review these documents and Federal CISO’s don’t like to put their name on the line certifying the solution for everyone to challenge. There are many vendors seeking compliance and very few agencies willing to sponsor them. If a Federal agency would like to have access to a SaaS solution, they invest all that time and resources along with the company investing, and maybe in a year or 18 months they begin their implementation. The bar is so high that most Federal agencies just do without. The imbalance between SaaS companies looking for sponsorship and the number of Federal agencies willing to sponsor FedRAMP compliance is enormous. Federal agencies are left to use their inferior, outdated, and possibly less secure on-premises existing solutions.

There is another way to get a FedRAMP certification through the Joint Authorization Board (JAB), but that process takes even longer, so I won’t elaborate on it. The Government likes to talk about the “reuse” of these certifications, but only 7% of CSPs have 50 or more authorizations, led by Amazon, Akamai, Microsoft, and Cisco/Okta.

The ultimate irony is that just because a SaaS offering is FedRAMP compliant, it does not mean that an agency can start using it. In fact, the ATO’s are not reciprocal. Each CISO must review the 500 pages of documentation held in the FedRAMP repository and sign off that it meets their agency’s requirements. Each CISO is wholly responsible for the solutions that they deploy. It is not good enough that another CISO approved the software. Wait a second! Wasn’t the purpose of FedRAMP to comply once and use many? The recently passed FedRAMP Authorization Act seems to have resolved this issue, but we’ll have to wait and see how it’s implemented.

Now that we better understand the ecosystem of the federal marketplace, in the next installment of this two-part series, I will discuss the implications for startups and the government and how startups can hope to unlock one of the most lucrative marketplaces.

[1] https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/saas-market-report

[2] https://www.spendesk.com/blog/saas-statistics/

[3] https://www.bvp.com/atlas/state-of-the-cloud-2020